This article was originally published on InfoQ

Key Takeaways

- Increasing self-awareness and context awareness for the self and others is the most important activity for anyone wishing to be relevant.

- People perceive experiences, interactions, and context differently. The most appreciated leaders are both aware of this and understand its significance.

- Understanding what specific needs people have to take steps forward and make progress is highly appreciated.

- Complexity and trivialisation are prevalent in tech companies. Recognising complex situations when people trivialise them is a valuable trait.

- Outcomes in a specific complex situation are effects of the interactions between actors and the organisation’s capabilities.

Many people refer to themselves as leaders and expect to lead in organizations today. Based on my observations and speaking with other professionals, it’s fair to say that far from all are considered great.

People’s perceptions and expectations of leadership require a leader to understand their own contextual significance. Additionally, trivialisation often unknowingly stands in the way of progress in complex situations.

During my work with various tech organizations over the years, I’ve experienced complexity-related challenges. Fortunately, I’ve observed some specific traits that distinguish people who repeatedly provide appreciated and appropriate leadership.

Leaders and Leadership

To spot a “great leader,” I use the most fundamental comment I’ve come across about what leadership entails.

Leadership is “movement toward something.” Without movement or direction traveled, there’s no leadership.

I’ve found this framing particularly useful because it’s context-free, meaning that its practical manifestations are context specific. Being a leader of a country, football team, shoe factory, or organisation that uses software as a tool to provide utility implies differences and similarities, both conceptual and practical. The conditions that enable a specific organisation to have momentum vary with context.

From a professional standpoint, I’m most familiar with contexts that are socio-technical in nature. Specifically, SaaS companies experiencing complexity and uncertainty while organising humans to use technology to provide utility and shareholder value.

In my work, I observe what distinguishes people who provide appreciated and appropriate leadership in the mentioned context. This, together with mentioned framing of leadership, helps me explore and practice the nuances and specifics of leadership.

Undoubtedly, people across organisations have expectations of “leaders.” In a general sense, they expect them to lead. In my experience, this entails a diverse set of expectations from various people within a collective or shared context. The most common expectations I’ve come across are providing answers and clarity, guidance, context, direction and vision, structure, and accountability.

Think of how expectations are entangled with the framing of leadership. People seem to have different specific needs to take steps toward something and make progress. My experience is that a person’s historical experiences significantly influence their needs, which vary with context. People’s awareness about themselves, a specific situation, and others vary. So what people think is needed is sometimes not relevant or appropriate. These are some reasons I’ve found the specifics of leadership challenging, to say the least.

Some of the sources that I’ve found particularly helpful when managing these challenges—understanding individual and contextual needs—are SCARF by David Rock and Wardley Mapping.

The SCARF model relies on social neuroscience research and has proven very useful in understanding an individual’s needs when interacting with other humans and in context. It suggests that a human’s cognition will increase if the threat to its status, certainty, autonomy, relatedness, and fairness is decreased.

SCARF provides clues to what specific biases drive specific threat-related interactions within a team and the organisation. I’ve specifically seen team members and managers realise, with the help of surveys, that a lack of relatedness and sense of belonging toward one another was preventing them from making timely decisions. Another realisation was that people chose to leave a specific infrastructure team because they lacked clarity on how they could improve internal developer experience while not having enough autonomy and status to influence the technical architecture direction.

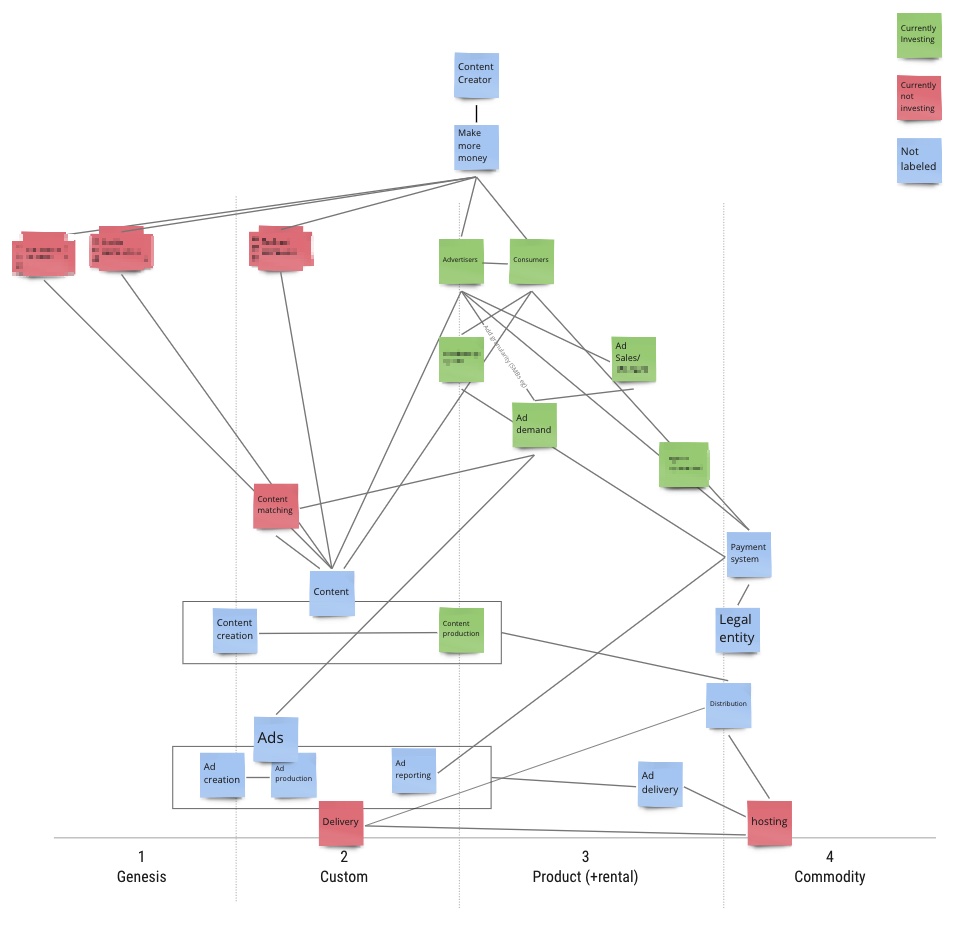

The Wardley Mapping practice has been very useful in simplifying the complexity of an organisation’s experienced context, bringing forth insights into what capabilities are key in a particular situation and essentially generating contextual and strategic awareness.

Concretely, a product director and I, for example, have used it to familiarise ourselves with a new business context. It provided us insight into the needed capabilities to fulfil crucial user expectations and the capabilities our teams were investing in developing. We also realised that it would be more effective for the business to invest in capabilities that we currently weren’t.

Effects of trivialising complex situations

Another viewpoint that comes to mind when attempting to spot “great leaders” is my first-hand work with organisations. Many companies I’ve been fortunate to work with in the past ten years have found it difficult to predict outcomes with certainty. They’ve experienced many factors that affect circumstances, an abundance of ambiguity, and a lack of consistency. When faced with concrete product challenges, I’ve seen employees with know-how generate competing hypotheses and disagree with how to respond. Subsequently, varied responses have generated plenty of desired outcomes and unintended consequences. These companies have experienced complexity and uncertainty.

In this context, I’ve noticed that trivialisation seems to be fairly prevalent, most clearly noticeable from people’s repeated use of statements such as “We just need to improve our communication,” “We just need to have a clear process for this,” and “We just need to use common sense, and then things will improve.” Mind you that the intent of these statements is mainly to help improve a situation. Unfortunately, ignorance leads to opposite effects.

In my experience, trivialisation fundamentally sets false expectations and hopes. It encourages a collective to search for a single root cause or crystal clear explanation for their observed experiences and consequences. It also enables a belief that “the problem” and “the solution” are either found in a process or specific individuals. In complex situations, a multitude of factors is both influential and entangled. Causation is not linear, nor can it reveal a solution or prediction (with certainty) by analysis. Outcomes and results in a given situation are effects of the interactions between actors and the organisation’s capabilities.

Trivialisation diminishes the opportunity to discover significant key insight—through safe-to-fail experimentation—and the emergence of appropriate and sustainable practices.

Another fundamental effect I’ve observed is that it tends to undermine the agency of a system (i.e., it considerably diminishes both people’s ability to improve circumstances and the organisation’s ability to adapt).

I’m still learning about the effects trivialisation has in complex cases. Dave Snowden’s work, in particular, continues to be a source of learning for me, and I encourage anyone interested to research his and Cognitive Edge’s work on the subject.

Signs that distinguish “Great Leaders”

From a general standpoint, I’ve observed that people who are perceived as “great leaders” have a profound positive impact on their surroundings. In the context of complexity, they focus on creating conditions and adopting tools for the organisation to lead appropriately and sustainably. This tends to increase agency, individual and collective awareness, shared understanding, and collective intelligence. It particularly increases awareness and a shared understanding of how people experience and perceive the present versus mainly focusing on envisioning a future desired state, goals, or circumstances.

“Great leaders” have realised that it’s not enough to provide or surface a compelling vision. They’ve realised that it’s fundamental for a collective to understand their current position when managing complexity and navigating toward a future goal.

They focus on understanding the present, including the position, landscape, circumstances, and dynamics that occur. They create conditions that are conducive to collective sense-making and agency. This tends to increase the awareness of what options are available for the collective. While also encouraging reasoning and practical exploration of what options are appropriate.

With this in mind, I’ve found several signs that distinguish people who provide appreciated and appropriate leadership. There are five in particular that I would like to elevate; however, by no means do they paint an integral picture. The main reason for choosing these is that my observations make me believe that not enough people currently display these signs.

Identifying positives

Plenty of people share their views on what’s not working or could be improved in a situation, repeatedly pointing out what prevents a group of people, team, or product from becoming more successful. While relevant, it’s not effective enough. More people should identify and share what’s working adequately in a situation.

Despite how trivial it may sound, it could be as “simple” as what a peer agile coach of mine once did: she worked with a team that had great technical challenges with scaling and trouble coming to an agreement or consent. The team, managers, and other coaches acknowledged this fact. Instead of doing the same, she shared her observation and appreciation for team members’ openness toward each other and that they were respectfully sharing their thoughts. This injected enough positivity to unlock a path toward improvement by safely experimenting.

Key knowledge is gained by acknowledging the present and the efforts spent creating it. Doing so encourages incremental, iterative and continuous improvements. It also increases the chances of breaking down conditions into steps with distinct utility and purpose.

Awareness of present

As I mentioned previously, I’ve also noticed that a commonly accepted perception of a “great leader” is that they are a visionary—someone who can articulate a clear and compelling future goal. While people appreciate this ability, leaders who rely heavily on visions and goals fail to provide appropriate guidance on taking the practical path toward the future. People perceive experiences, interactions, and context differently. The most appreciated leaders are both aware of this and understand its significance, leading them to increase collective awareness of how they and others experience and perceive the present. This particularly helps bring into plain view the specific conditions that a collective is surrounded by. It also highlights what options are more or less feasible for the collective at any given point. They also keep options open for as long as feasibly possible.

For example, when I worked at Spotify, there were at one point three data infrastructure teams with the overall purpose of collecting user data for financial reporting and product performance. They could not do so reliably, despite all teams clearly understanding their own and overall vision. It took a few experienced leaders to jointly create awareness that the current technical boundaries between the teams created friction that prevented them from making necessary improvements. New boundaries were created by organising the same people into three alternative teams, thus unlocking progress.

Analogies and varied perspectives

Complex situations and challenges are tremendously difficult to manage, inevitably causing people to become puzzled, confused, or stuck. Soliciting and sharing conceptual similarities from adjacent and distant knowledge domains, using analogies, is appropriate to unlock progress. This not only allows people to look at a situation from an alternative perspective, but it also becomes easier to avoid using redundant approaches and overlearned behaviour or habits.

Surprisingly, perhaps the most effective analogy I’ve used was with a manager who had tried to get a team to improve their management of technical debt for quite some time. The team was, for various reasons, not dealing with tech debt that was contributing to repeatable critical bugs and outages. Unfortunately, the manager didn’t have enough relevant context and knowledge to help the team hands-on. So, to get the team to work on their tech debt, the manager had mainly been nudging them and arguing for the importance of managing tech debt without enough of the desired effect.

Hearing him talk about his struggles, I spontaneously shared an experience my neighbours had during the summer. They noticed that their hedge around the garden had been invaded by aphids. The aphids were spreading exponentially and, without intervention, would eat most of the leaves. So they asked their six-year-old daughter if she could collect as many ladybugs as she could find and place them on their hedge. Since she adored ladybugs, she excitedly spent roughly 60 minutes doing so. After a week or so, it was clear that the ladybugs had been effective. The population of aphids was no longer an issue, and the hedges were saved.

This story made the manager think of a particular developer in a different team he’d previously worked with who had relevant experience and would be excited to work on the particular challenges. His involvement influenced positive change, and critical bugs and outages became significantly less frequent.

Leaning into the unexpected

Managing complex situations and challenges very seldom goes precisely as expected and inevitably leads to unexpected outcomes or unintended consequences. Appreciated and appropriate leadership entails leaning into the unexpected and treating unexpected outcomes and unintended consequences as great indicators for gaining insights. This invites people’s curiosity and openness to learn and increases the likelihood of identifying when seemingly insignificant things have tremendous importance.

One organisation I worked with experienced that a specific effort to increase a particular business outcome exceeded expectations. At the same time, another effort to achieve a different outcome was failing, and its urgency was now critical. Senior management decided that an individual who had made key contributions to the successful outcome should refocus and join the failing effort. This highly appreciated individual (by peers, team members, and stakeholders) was also given increased mandate by senior management.

An increase in progress was observed mere weeks after this had taken effect. Besides this, dependency on a single individual had increased, as well as an increase of cynicism and decrease of empathy among several employees and managers.

Following others

Highly appreciated leaders also know when to follow others. They are comfortable taking a step back when appropriate, avoiding making the collective overly dependent on a single source, such as themselves. And they create conditions that are conducive to learning, agency, and collective intelligence.

The most vivid display of this trait I’ve experienced so far is by the Spotify founders Daniel Ek and Martin Lorentzon, both in their own unique way.

When I interacted with Ek or saw him interacting with others, he always took the time to acknowledge, appreciate, and engage with input.

He connected you with people who either had more knowledge and insight than himself or were in a more appropriate position to influence progress. He did not hesitate to publicly share when he or his direct reports were unclear about a particular topic and pointed at sources of potentially new insight. Additionally, he demonstrated an ability to understand someone else’s perspective and shared the learnings he made from others.

Lorentzon would enthusiastically and candidly declare to new hires that Spotify didn’t need him as much as the company needed them, acknowledging that everyone had been hired for their specific experience. He also encouraged everyone to enrich the company, contribute to its outcomes, learn from others, and use those learnings and connections to start their own companies.

Additional signs

Besides these five signs above, I’ve also observed another handful of signs that are worthy of attention, which you can find in the provided illustration.

In aggregate, the illustration still doesn’t paint an integral picture. That said, if a leader displays most of these signs, it could indicate they provide appreciated and appropriate leadership.

Additional sources of learning

Besides my work experience, there are some key people and work that influence my thinking and practice in the context of this article. Hopefully, you’re already familiar with some of their work, but if not, I highly recommend everyone take a closer look.

- Klara Palmberg’s doctoral thesis—Beyond Process Management

- Esther Derby on contextual change—7 Rules for Positive, Productive Change

- Dave Snowden on context awareness and navigating complexity—Cynefin framework

- David Epstein on generalists strengths during complexity—Range

- John Kay and Mervyn King on decisions during uncertainty—Radical uncertainty

- Aaron Dignan on complexity conscious—Brave New Work